Flight (2022)

Whooper Swan - Inch Levels, Donegal

In the year 1845, 8,259 people were buried in Glasgow. In the year 1847, that number had increased dramatically to 18,889. What happened? In 1845 blight (phytophthora infestans) destroyed the potato crop in Ireland and in 1846 the same thing happened again, this time also affecting the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Although the blight abated temporarily in 1847, so little seed had been planted that year that the yield was meagre. In short, widespread starvation meant that many thousands of migrants arrived in Glasgow from Ireland for several years after 1845. At the peak of summer 1847 up to 10,000 Irish people arrived during some weeks. The condition of those arriving was often wretched. People were malnourished and diseased and had little or no money with which to provide food and shelter for themselves. Those who could afford it quickly made for Liverpool and then America. The poor begged and threw themselves upon the charity of the Catholic Church. The clergy did everything they could to assist, several priests in Glasgow died of infectious diseases in the process, but they could not avert the mortality crisis that more than doubled the city’s burial statistic within two years.

Mary, Tragumna, Cork

Ireland is the only country in Europe where the population today is less than it was prior to 1845. In the space of seven years, one million people died and more than that number emigrated. In the aftermath of the famine people kept on leaving Ireland mainly for North America, but many also kept finding their way to Scotland. Tragically there was food aplenty in Ireland during the famine, so much so that mass exports to England of cereal crops and livestock continued throughout the crisis. Governments in other affected countries stopped food exports and temporarily banned distillation of alcohol from grain. The lassiez faire Westminster government was however reluctant to intervene. Government schemes did establish temporary work programmes and soup kitchens, but these were dropped as new laws were passed switching responsibility for famine relief from government to local landowners. Although Britain was the richest country in the world at the time, the government effectively washed its hands of the problem of its own starving citizens. Landlords were unwilling or unable to meet the cost of famine relief at a time when rental income was collapsing. They resorted to mass evictions, and in some cases assisted migrations, to rid themselves of their impoverished tenants. Workhouses, the last resort of the poor, became vastly overcrowded breeding grounds for famine related diseases. Even in the more industrialised urban centres of Belfast and Dublin poor people, Catholic and Protestant alike, starved to death.

Healy's Pass - Cork/Kerry border

When the Irish first arrived in the West of Scotland the economy was relatively stagnant. There was significant opposition amongst the local population to the sudden and continuing arrival of poor hungry Irish folk competing for food, shelter and employment. Scottish newspapers at the time were blatantly racist toward the Irish, helping to inflame an already hostile environment. Things changed for the better after 1848 when the pace of industrialisation in the central belt quickened, assisted by its rich local coal deposits. Glasgow flourished and staked its claim to be the ‘second city of the Empire’. Irish immigrants played their part in laying Scotland’s rail network, in literally building the Victorian city of Glasgow that we know today, and in constructing the great pipeline that finally secured the city’s fresh water supply from Loch Katrine in the Trossachs. Within a few generations the Irish became integrated into Scottish society but it has always been a two way street. People were on the move between Ireland and Scotland before borders were established. Family connections and political developments ensure that the process of ebb and flow continues to this day.

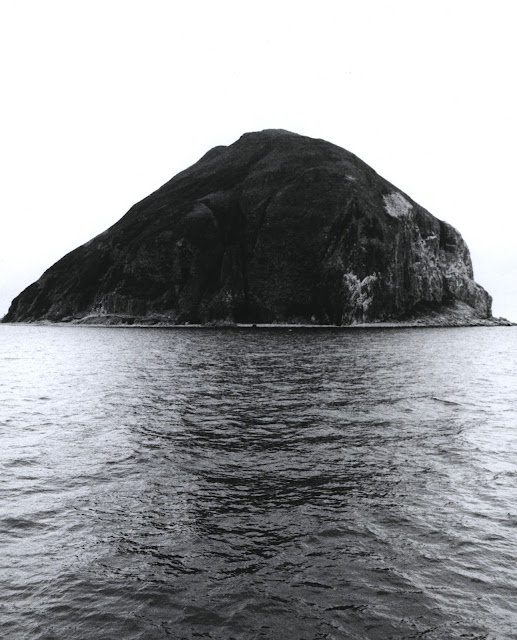

Ailsa Craig (Paddy's Milestone), Clyde Estuary

There are three famine memorials in the West of Scotland, all established during the twenty first century: a Celtic cross at Carfin Grotto, an upturned boat on Glasgow Green, and a statue of suffering victims of An Gorta Móroutside St Mary’s Church on Abercrombie Street. These symbolic memorials provide dedicated spaces where we can reflect on the history of the Great Famine. For people with Irish or Gaelic heritage, there we can also mourn the great losses of our ancestors and the legacy of those losses. But remembering and mourning, healing even, are not enough. The wreckage of the past is piling high behind us as ‘progress’ rushes us forward. Honouring the victims of An Gorta Mór requires learning from the past and applying those lessons to the challenges of today.

More people are in flight today than ever before. 281 million people now live outside the country of their birth. War, famine, climate change and grotesque inequality are all driving people to risk perilous journeys in the hope of better lives elsewhere. Rather than welcome refugees the West often criminalises or repels them, building walls and turning back vessels at sea. The latest tactic is outsourcing. If asylum seekers arrive without prior approval in the UK, often from countries previously occupied by Britain, the government’s current plan is to send them to Rwanda. In the first three months of the war in Ukraine, Britain welcomed no less than 60,000 Ukrainian refugees. The fact they were white Europeans meant they were treated very differently than their counterparts from countries in the Middle-East, Africa and Asia. This rapid accommodation proved what is possible in a relatively wealthy country of more than 67 million people when racism is not in play and humanitarianism overcomes selfish economic interest.

Malin Head, Donegal

Immigration has long been a jugular issue in British politics due to the country’s ongoing legacy of imperialism and the racism that underpins it. Many citizens of Britain’s former colonies see Britain as their natural migratory destination. Until the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act, all Commonwealth citizens had an automatic right to settle in the UK. Since then, Labour and Conservative parties have vied with one another in passing ever more restrictive anti-immigrant legislation. In the wake of Brexit, this year’s Nationality and Borders Act sets a new standard in the inhumane treatment of people seeking refuge. This legislation should be resisted by any means necessary and ultimately overturned. We should welcome refugees no matter how they arrive and never succumb to demands that we send people, against their will, to countries who have been paid to receive them like human cargo.

* The Flight project was exhibited at Street Level Photoworks in Glasgow as a major solo show August - October 2022. A video of the exhibition can be viewed on the link here:

All images © Frank McElhinney

My mother is a McElhinny. Her people were in Donegal up until the famine. They then emigrated to Canada. I am very interested in the movement of McElhinnys within Ulster prior to the 1800s. I live in New York and we are making a trip to Argyllshire in October. I am gutted to have missed this gorgeous exhibit. May I ask whereabouts your branch of the McElhinneys are from?

ReplyDeleteRichard, good to hear from you. My family on the McElhinney side came from Roosky (near Castle Forward) and from Falcaragh on the coast. If you are over in Argyll during the first half of October you can catch a version of the show at the Rockfield centre in Oban (open every day 10am till 4pm until the 15th). All the best, Frank

Delete